Meiosis: The Basis of Sexual Reproduction and Genetic Diversity

Meiosis is a specialized form of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in the formation of four genetically unique haploid cells from one diploid cell. This process is fundamental to sexual reproduction in eukaryotic organisms, including animals, plants, fungi, and some protists. Meiosis not only ensures the maintenance of a stable chromosome number across generations but also introduces genetic variation, which is crucial for evolution and adaptation.

Overview of Meiosis

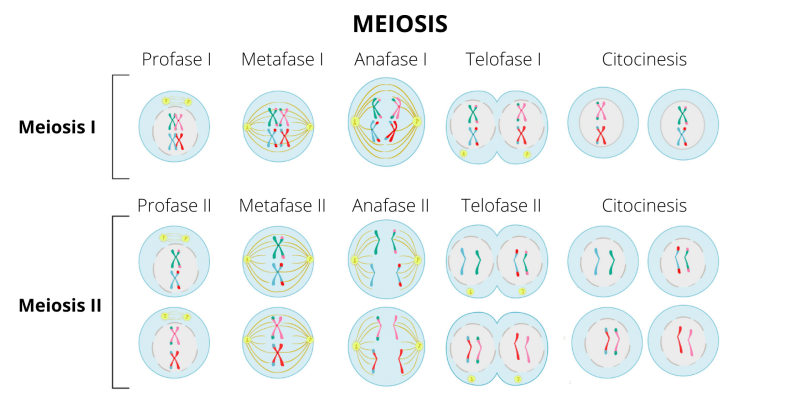

Meiosis consists of two sequential divisions: Meiosis I and Meiosis II. Each of these divisions has distinct stages resembling those of mitosis, but with unique processes that facilitate the reduction of chromosome number and the recombination of genetic material.

Meiosis I: Reductional Division

Meiosis I is termed the reductional division because it reduces the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n). It includes the following stages:

-

Prophase I :

-

Leptotene: Chromosomes condense and become visible.

-

Zygotene: Homologous chromosomes begin to pair up in a process called synapsis, forming tetrads (bivalents).

-

Pachytene: Crossing over occurs, where homologous chromosomes exchange genetic material, creating genetic diversity.

-

Diplotene: Synaptonemal complex dissolves, and homologs start to separate, remaining attached at chiasmata (sites of crossover).

-

Diakinesis: chromosomes further condense, and the nuclear envelope breaks down, preparing for metaphase I.

-

-

Metaphase I:

- Homologous chromosome pairs (tetrads) align at the metaphase plate.

- Microtubules from opposite spindle poles attach to kinetochores of homologous chromosomes.

-

Anaphase I:

- Homologous chromosomes are pulled to opposite poles, but sister chromatids remain attached.

- This separation reduces the chromosome number by half.

-

Telophase I and Cytokinesis:

- Chromosomes reach opposite poles.

- Nuclear envelopes may re-form briefly.

- The cell divides into two haploid daughter cells, each with half the original chromosome number.

Meiosis II: Equational Division

Meiosis II resembles mitosis, where sister chromatids are separated, resulting in four haploid cells.

-

Prophase II: Chromosomes condense again, and a new spindle apparatus forms. The nuclear envelope, if it reformed during telophase I, breaks down.

-

Metaphase II: Chromosomes align at the metaphase plate. Spindle fibers attach to kinetochores of sister chromatids.

-

Anaphase II: Sister chromatids are finally separated and pulled to opposite poles of the cell.

-

Telophase II and Cytokinesis: Chromatids reach the poles, and the nuclear envelope reforms around each set of chromosomes. The cytoplasm divides, resulting in four genetically unique haploid cells.

Genetic Diversity in Meiosis

Meiosis introduces genetic variation through two primary mechanisms: crossing-over and independent assortment.

Crossing-Over: Occurring during prophase I, crossing-over involves the exchange of genetic material between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes. This recombination generates new combinations of alleles on each chromosome, increasing genetic diversity.

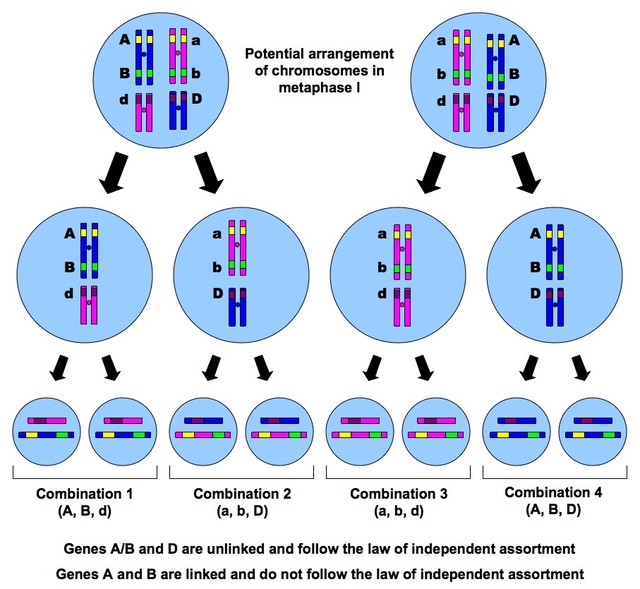

Independent Assortment: During metaphase I, homologous chromosome pairs align randomly at the metaphase plate. This random orientation results in the independent segregation of maternal and paternal chromosomes into gamete. The number of possible combinations is given by 2^n, where n is the haploid number of chromosomes. In humans, with a haploid number of 23, this results in over 8 million possible combinations.

Significance of Meiosis

Meiosis is crucial for sexual reproduction and has several important roles:

-

Reduction of Chromosome Number :

The reduction of chromosomes number is fundamental to sexual reproduction. If meiosis did not halve the chromosome number, fertilization would result in a doubling of chromosomes with each generation, leading to polyploidy and potential genomic instability. By maintaining a consistent chromosomes number, meiosis ensures that offspring have the same diploid chromosomes number as their parents, which is crucial for the stability and function of the genome.

-

Genetic Diversity through Crossing-Over :

Crossing-over occurs during prophase I when homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange segments. This process creates new allele combinations, enhancing genetic diversity. This diversity is essential for populations to adapt to environmental changes and for the process of natural selection to drive evolution. The novel genetic combinations resulting from crossing-over can lead to new traits that may be advantageous for survival and reproduction.

-

Independent Assortment of Chromosomes :

Independent assortment occurs during metaphase I when homologous chromosome pairs align randomly at the metaphase plate. This randomness in alignment means that the combination of chromosomes that each gamete receives is unique. This process further contributes to genetic diversity by ensuring that each gamete has a different set of chromosomes, combining alleles in novel ways.

-

Repair of DNA Damage :

During prophase I, homologous recombination not only facilitates genetic exchange but also repairs DNA double-strand breaks. This repair mechanism is vital for maintaining the integrity of the genome. Cells that fail to repair DNA damage can pass on mutations that may be harmful. By incorporating DNA repair processes, meiosis ensures that genetic material is accurately transmitted to the next generation.

-

Elimination of Harmful Mutations :

Sexual reproduction and meiosis help eliminate harmful mutations from the population. Harmful recessive mutations can be hidden in heterozygous individuals (carriers) but will be expressed in homozygous recessive individuals. These individuals may have reduced fitness and are less likely to reproduce, thereby reducing the frequency of these harmful mutations in the population over time.

-

Production of Haploid Cells :

The production of haploid gamete (sperm and egg) is essential for sexual reproduction. These gamete combine during fertilization to form a diploid zygote, restoring the diploid chromosome number and combining genetic material from two parents. This process not only maintains chromosome number but also introduces genetic variation, which is critical for the adaptability and evolution of species.

-

Role in Sexual Reproduction :

Meiosis is crucial for sexual reproduction, which generates offspring with unique genetic identities. This genetic uniqueness is important for the survival of species, as it allows populations to adapt to changing environments. Offspring with diverse genetic backgrounds may possess advantageous traits that improve their chances of survival and reproduction.

-

Formation of Spores in Plants and Fungi :

In plants, meiosis produces spores that develop into gametophytes, which then produce gamete through mitosis. In fungi, meiosis produces spores that can develop into new organisms. These reproductive strategies are crucial for the life cycles of plants and fungi, allowing them to reproduce and spread. Spores are also a means of surviving harsh conditions, as they can remain dormant until favorable conditions arise.

-

Facilitation of Evolution :

By generating genetic diversity, meiosis facilitates evolution. Genetic variation within a population provides the raw material for natural selection to act upon. This variation allows populations to adapt to changing environments, leading to the evolution of new species and the diversity of life forms on Earth. The ability to evolve and adapt is crucial for the long-term survival of species in a dynamic world.

-

Prevention of Polyploidy :

Meiosis ensures that gamete receive only one set of chromosomes, preventing polyploidy. While polyploidy can be beneficial in some plants and lead to speciation, it can cause problems in animals, such as developmental abnormalities and infertility. By maintaining a stable chromosome number, meiosis ensures proper development and function of the resulting offspring.

Meiosis in Different Organisms

While the basic process of meiosis is conserved across eukaryotes, there are variations in how different organisms execute meiosis.

In Animals: Meiosis results in the production of gamete (sperm and eggs). Spermatogenesis in males produces four viable sperm cells from each primary spermatocyte, whereas oogenesis in females produces one viable egg and three polar bodies from each primary oocyte.

In Plants: Meiosis leads to the formation of spores, which then undergo mitotic divisions to form gametophytes. In flowering plants, meiosis in the anthers produces pollen grains (male gametophytes), and meiosis in the ovules produces embryo sacs (female gametophytes).

In Fungi and Protists: Meiosis often results in the formation of spores that give rise to haploid organisms. These haploid forms can undergo mitosis and produce gamete that fuse to restore the diploid state.

Errors in Meiosis

Errors during meiosis can lead to chromosomal abnormalities, which are significant causes of genetic disorders and miscarriages.

Nondisjunction: This occurs when homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate properly during anaphase I or II. This results in gamete with abnormal chromosomes numbers, leading to conditions such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Turner syndrome (monosomy X), and Klinefelter syndrome (XXY).

Translocations and Inversions: Structural changes to chromosomes, such as translocations (exchange of segments between non-homologous chromosomes) and inversions (reversal of a chromosome segment), can also occur during meiosis, potentially leading to genetic disorders or cancer.

Meiosis FAQ

Meiosis contributes to the prevention of aneuploidy (abnormal chromosome number) through precise mechanisms of chromosome pairing, segregation, and checkpoints that monitor proper chromosome alignment and separation. The spindle assembly checkpoint ensures that chromosomes are correctly attached to the spindle fibers before anaphase. However, errors can still occur, leading to nondisjunction, where homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids fail to separate properly. This results in gametes with an abnormal number of chromosomes, which, upon fertilization, can lead to conditions such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Turner syndrome (monosomy X), or Klinefelter syndrome (XXY).

Cohesins are protein complexes that hold sister chromatids together, ensuring proper chromosome alignment and segregation. In meiosis, cohesins are also involved in holding homologous chromosomes together during prophase I. Separase is an enzyme that cleaves cohesins, allowing for the separation of sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes. In meiosis I, cohesins along the chromosome arms are cleaved by separase, enabling the separation of homologous chromosomes, while cohesins at the centromeres are protected by the protein shugoshin. In meiosis II, cohesins at the centromeres are cleaved, allowing sister chromatids to separate. The regulation of cohesin cleavage by separase is tightly controlled by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), ensuring the sequential separation of chromosomes during meiosis.

The stages of meiosis ensure accurate chromosome segregation through a series of coordinated events and checkpoints:

- Prophase I: Homologous chromosomes undergo synapsis and crossing-over, ensuring proper pairing and recombination.

- Metaphase I: Homologous chromosomes align at the metaphase plate, with each pair oriented towards opposite poles. The spindle assembly checkpoint verifies that all chromosomes are correctly attached to spindle fibers.

- Anaphase I: Homologous chromosomes are separated to opposite poles, reducing the chromosome number by half.

- Telophase I and Cytokinesis: Cells divide to form two haploid cells.

- Prophase II to Metaphase II: Chromosomes condense and align again.

- Anaphase II: Sister chromatids are separated, ensuring each gamete receives one copy of each chromosome.

- Telophase II and Cytokinesis: Cells divide again, resulting in four haploid gametes.

Checkpoints during meiosis, such as the spindle assembly checkpoint, monitor proper chromosome attachment and alignment, ensuring that segregation errors are minimized and genetic integrity is maintained.

Meiosis I and meiosis II are two distinct stages of meiotic division with different processes and outcomes:

-

Meiosis I:

- Reductional Division: Chromosome number is halved from diploid (2n) to haploid (n).

- Homologous Chromosome Separation: Homologous chromosomes are separated, reducing the chromosome number by half.

- Unique Events: Includes crossing-over during prophase I and independent assortment during metaphase I.

- Outcome: Two haploid cells with duplicated chromosomes (each chromosome consists of two sister chromatids).

-

Meiosis II:

- Equational Division: Chromosome number remains haploid (n) throughout.

- Sister Chromatid Separation: Sister chromatids are separated, similar to mitosis.

- Events: No crossing-over; straightforward separation of chromatids.

- Outcome: Four genetically unique haploid cells, each with a single set of chromosomes.

Crossing-over occurs during prophase I of meiosis when homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange segments of genetic material. This process involves the formation of the synaptonemal complex, which aligns homologous chromosomes closely together, allowing for the precise exchange of genetic material between non-sister chromatids. The resulting recombinant chromosomes contain a mix of alleles from both parents, generating new combinations of genes. This genetic recombination increases the genetic diversity of gametes, which is crucial for the adaptation and evolution of species by providing a broader range of genetic traits for natural selection to act upon.

Conclusion

Meiosis is a vital biological process that underpins sexual reproduction and contributes to genetic diversity. By reducing the chromosome number and facilitating genetic recombination, meiosis ensures the stability of species' genomes across generations and fuels evolutionary processes. Understanding the intricacies of meiosis not only sheds light on fundamental aspects of biology but also provides insights into the causes and potential treatments for various genetic disorders. The precision and complexity of meiosis exemplify the remarkable mechanisms that sustain life and its diversity.

Here are two article on the same topic: